By Andy Mao, National Elder Justice Coordinator, U.S. Department of Justice

This guest post is part of Healthy People in Action, a blog series highlighting how key partners use the Healthy People framework in their work, form cross-sector collaborations, and address social determinants of health to help achieve health equity.

In this post, the author discusses addressing Elder Abuse to improve health outcomes for older adults and promotes aging in place. The Elder Justice Initiative at the U.S. Department of Justice provides training and resources to help promote the health and well-being of older adults.

The Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion has hosted 3 national symposiums on healthy aging and the social determinants of health for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and has collaborated with the Elder Justice Initiative to bring awareness to important issues facing older adults.

The Elder Justice Initiative (EJI) joins our partners, the Administration for Community Living (ACL) and ODPHP, in commemorating May as Older Americans Month.

The study of the social determinants of health (SDOH) has identified how social factors contribute to poor (and often inequitable) health outcomes. Fortunately, many of the social and environmental factors that contribute to poor health outcomes are at least, to some extent, modifiable. Multiple, nonmedical factors (e.g., interpersonal relationships, early adverse childhood experiences, neighborhood conditions) have also been identified in this body of work.

Another factor that contributes to poor health outcomes is elder abuse.[i] Though typically not associated with the SDOH literature, elder abuse is a form of interpersonal violence[ii] and as such falls under the rubric of SDOH.

Elder abuse is defined as an intentional act or failure to act by a caregiver or another person in a relationship involving an expectation of trust that causes or creates a risk of harm to an older adult (typically defined as age 60 years and older).[iii] Elder abuse comprises 5 subtypes: physical abuse, sexual abuse, psychological abuse, caregiver neglect, and financial exploitation and fraud.[iv]

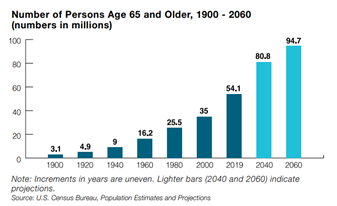

Certainly not all older adults experience elder abuse, but annually at least 15 percent of older adults do.[v] Given that in 2019, the population age 65-plus was 54.1 million — 30 million women and 24.1 million men — or 16 percent of the U.S. population, and given that the number is expected to reach 21.6 percent by 2040,[vi] between 15 million and 20 million older Americans will likely experience elder abuse each year. And that number is only expected to grow.

The consequences associated with elder abuse are expansive, but clearly many are associated with poor health outcomes. Research has linked elder abuse directly to injury, institutionalization, hospitalization, poor health, and even mortality. Indirectly, forms of elder abuse — such as financial exploitation — may inhibit health care visits and result in an inability to purchase prescriptions, and the financial strain associated with economic loss takes a toll on health.

Addressing elder abuse may contribute to better health outcomes for older adults while promoting aging in place. Many approaches can be taken, but one of the impediments to intervening is simply identifying elder abuse in the first place. There are multiple reasons why, but older adults are often reluctant to self-report. Health care providers are well positioned to observe the indicators of elder abuse. To be clear, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force does not endorse universal screening for elder abuse,[vii] but it does not prohibit health care providers from being aware of the warning signs and addressing elder abuse when it is observed.

The National Collaboratory to Address Elder Mistreatment is an exciting project working to ensure that older people seen in emergency rooms, including in hospitals with limited resources, are assessed for potential mistreatment and receive appropriate treatment and referral. Efforts such as the National Collaboratory ensure that health care providers know the red flags of elder abuse and how to respond. The keen observation and awareness of health care providers can save a life. The onus should not be, and is not, entirely upon health care providers, but they are a critical partner in the response to elder abuse.

Clinicians are encouraged to:

Talk to patients. Clinicians can empower patients to mitigate an abusive situation by simply talking about elder abuse. By being aware of the red flags of elder abuse themselves, clinicians can also facilitate their patients’ awareness of when someone is harming them, taking advantage of them, or defrauding them. Clinicians can learn more about communicating with patients in Talking Elder Abuse.

Document it. Clinicians can carefully document what they hear and see. The U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) has funded 2 projects related to documenting harms and injuries: a photographing injuries protocol[viii] was developed through Weill Cornell Medicine, and the Geriatric-Injury Documentation Tool (Geri-IDT)[ix] was developed through the University of Southern California. Oftentimes, it may take time for a person experiencing elder abuse to come forward, in which case the injuries may have healed or the individual’s recollection of the events may have changed. Contemporaneous documentation of injuries can compensate for these conditions.

Find help. Clinicians can learn where to reach out for help in their own community and will then also know where to refer their patients for help. Get to know caseworkers in the nearby adult protective services (APS) agency, and learn about APS by reading Adult Protective Services, What You Must Know. If the local APS agency is unknown, it can be found through the Eldercare Locator or the helpline at 1-800-677-1116.

The Elder Justice Initiative

The Elder Justice Initiative at DOJ is a partner in the fight against elder abuse. Collectively, the department develops training and resources for a range of professionals, including clinicians and public health professionals, available on the Elder Justice website. To prevent elder abuse, DOJ actively engages in raising public awareness of elder abuse generally, including the multitude of fraud schemes affecting older Americans.

During Older Americans Month, and every day, our shared goal is to ensure older Americans have access to justice, health care, and the ability to live with dignity and, to the extent possible, in their own home. Together, we can achieve this goal.

[i] Mouton, C. P., Haas, A., Karmarkar, A., Kuo, Y. F., & Ottenbacher, K. (2019). Elder abuse and mistreatment: Results from Medicare claims data. Journal of Elder Abuse & Neglect, 31(4–5), 263–280.

[ii] WHO (2002). World report on violence and health. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO.

[iii] CDC, 2016 (p. 28). Elder abuse surveillance: Uniform definitions and recommended core data elements. Atlanta (GA): National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

[iv] CDC, 2016 (p. 31–36) Elder abuse surveillance: Uniform definitions and recommended core data elements. Atlanta (GA): National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

[v] Yon, Y., Mikton, C. R., Gassoumis, Z. D., & Wilber, K. H. (2017). Elder abuse prevalence in community settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health, 5(2), e147–e156.

[vi] ACL (2021). 2020 Profile of Older Americans (stats p. 3 and the graph p. 5). Washington, D.C.: Administration for Community Living, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

[vii] U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (2018). Final Recommendation Statement — Intimate Partner Violence, Elder Abuse, and Abuse of Vulnerable Adults: Screening.

[viii] Bloemen, E. M., Rosen, T., Cline Schiroo, J. A., Clark, S., Mulcare, M. R., Stern, M. E., ... & Hargarten, S. (2016). Photographing injuries in the acute care setting: Development and evaluation of a standardized protocol for research, forensics, and clinical practice. Academic Emergency Medicine, 23(5), 653–659.

[ix] Kogan, A. C., Rosen, T., Navarro, A., Homeier, D., Chennapan, K., & Mosqueda, L. (2019). Developing the Geriatric Injury Documentation Tool (Geri-IDT) to improve documentation of physical findings in injured older adults. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 34(4), 567–574.

Comments (0)